|

Vice Admiral Sir Cecil P. Talbot, His Life Above And Below The Waves |

By Colonel John Talbot |

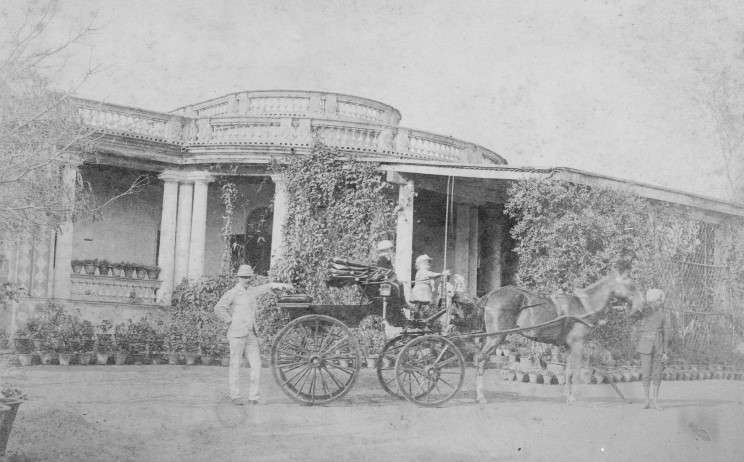

My father was born on 31 August 1884 in Bangalore, Southern India, and was named Cecil Ponsonby (Ponsonby was his mother's maiden surname). This was the period when Queen Victoria's Empire was at it's peak and India was virtually ruled by the British. There was a lot of trading between Britain and India and a British military presence contributed to public order. Cecil's father, Major F.A.B. Talbot, was Adjutant of the 43rd Light Infantry, a smart British Army regiment which later became the Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. He and his wife with their four boys Frank, Fitz, Cecil and Ted lived in the house in the photograph below; they must have lived a comfortable Sahib's life in the fresh air of the Nilgiri hills. |

|

Springfield House, Bangalore, India. |

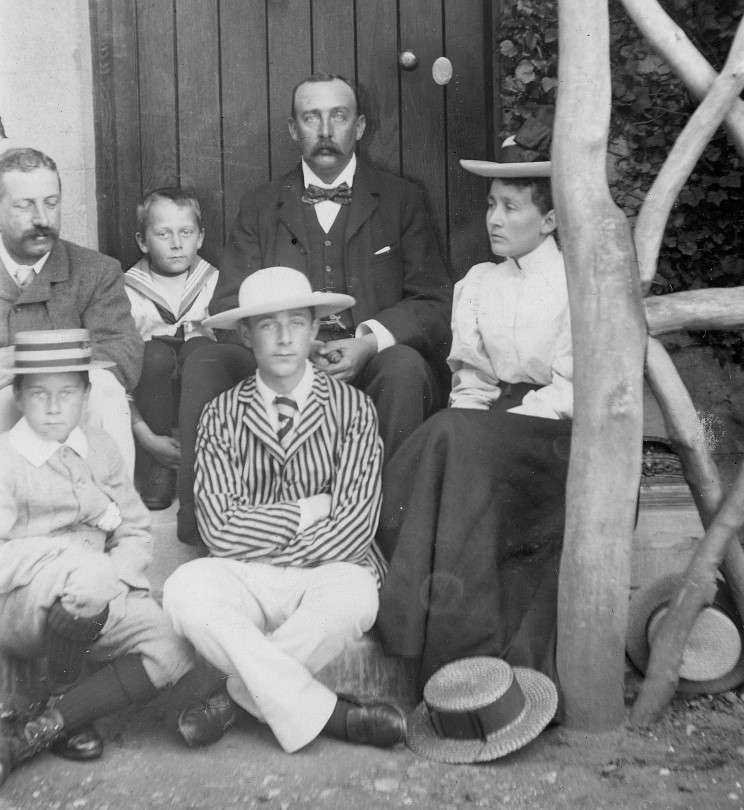

Soon after Cecil was born Major Talbot decided in about 1885 to bring his family back to England. His father, Admiral Sir Charles Talbot, K.C.B., had died previously and there was no family house for them in England, so they moved into Chilworth House in the village of Waterstock a few miles east of Oxford. The building is now a school with three acres of secluded land. The following photograph shows the family sitting in the porch. The boys went to Northaw School and Bedford School. |

|

The Talbot family at Chilworth House in 1896, from left to right; Reginald Fitzroy "Fitz", Edward Charles "Ted", Major

Francis Arthur Bouverie

Talbot, Alice Mary Beatrice Talbot (nee Lawford), Cecil (seated left) and Frank

Eustace George

(seated right). |

|

The drawing room at Chilworth House. |

|

Young Cecil and his bike. |

Later, Major Talbot became secretary of the Sports Club in St. James' Square. The parents moved to 89 Philbeach Gardens in London, which was the family house until the late 1920s. Cecil left the fold young. At the age of 13 he joined the Royal Navy as an officer cadet. This was before the Royal Naval College had been built at Dartmouth. The cadets had to live and learn in HMS Britannia, an old wooden line of battle ship moored in the river Dart. The training was tough, much the same as at public schools at that time but with more emphasis on maritime procedures and boat work. It seemed that life was permanently "At the Double". My father would only have been at home for short periods of leave until he passed out from the Britannia in August 1900. He was top of his year, winning the Chief Captain's Prize, an engraved Midshipman's dirk. In addition, he won the First Admiralty Prize of a boxed set of navigation instruments. These gave him a very good start for his career in the Royal Navy. |

The Chief Captain's Prize. |

The inscription; Chief Captains Prize Awarded to Mr. C. P. Talbot, HMS Britannia, August 1900. |

The early years of the new century saw big changes in ships. Sail and wood were giving way to coal and iron. British shipyards were busy building vessels not only for Britain but also for Japan. Germany and France were experimenting with submarines and airships, but the Royal Navy held back on these new weapons. There was a school of thought that submarines were improper, but he applied anyway to join submarines. Before that was allowed he had to serve in a seagoing surface ship, so in 1901 he joined his first warship, HMS Glory (12,500 tons) on the China station during the Boxer rebellions. The task was the control of the opium trade. For this purpose HMS Glory sailed 1,100 miles up the Yangtze River to Hankow, to give support to the troops ashore. |

My father distinguished himself one evening when he was in charge of a picket boat taking sailors to and fro. HMS Glory was moored midstream in the mile-wide, fast flowing, and muddy river. When returning after dark, one of the sailors missed his foothold and fell into the river, my father saw the danger at once and jumped into the river to hold the sailor afloat. Together they were swept downstream, but my father grabbed onto the anchor chain and was just able to hold tight until they were rescued by another boat. For this bravery he was presented by the Admiral with an engraved officers' sword, later he was also awarded The Royal Humane Society's Bronze Medal for saving life at sea (see Medals and Honours page). Two of my father's three brothers, Frank and Ted, were also involved with this "Boxer" war in China, in the 47th Sikh infantry regiment. |

The sword awarded to Cecil P. Talbot for his lifesaving effort. |

The inscription; Vice Admiral Sir Cyprian Bridge to Midshipman Cecil P. Talbot, R.N., Who saved a shipmate's life at risk of his own, HMS Glory, Hankow, 8 May 1903. |

| He then returned to Barrow-in-Furness in 1904 and joined the newly formed Submarine Branch. He served as an officer in early submarines such as A-11, B-2 and C-2. These early submarines were primitive and dangerous, as they ran on petrol and batteries, both of which could and did produce noxious gases. This of course was in addition to the inherently stale air of a submarine. |

My father played rugger whenever possible, until he was about 35, at scrum half. He played for the United Services Portsmouth. The photograph below shows the teams for the match against Trinity College, Dublin in November 1906, he is shown sitting bottom left cross legged. The standard can be judged by the fact that the TC Dublin team included eleven Internationals, and US Portsmouth six. Later Bob also played scrum half for the Navy and for Kent, and when he was abroad Frank took his place. |

|

In 1908 he attended an army balloon course, the first naval officer to do so. Then, in 1911, he was First Lieutenant of HM Airship No. 1, also known as Mayfly (see page 3), an experimental rigid airship intended for the Royal Navy for observation at sea. This was the first to be constructed for the Royal Navy, but unfortunately the structure was too weak and soon after being towed out of it's shed at Barrow-in-Furness the whole frame cracked up, and two years work was completely wasted. The crew and designers in the two gondolas had to swim for it. Cecil was formally commended for his role in preventing any casualties. |

On 12 August 1912 he was married, in Barrow-in-Furness parish church, to Bridget Bradshaw, daughter of the Mayor of Barrow. Sadly her mother had died previously, so there was space for all in their house, Fairfield. We still have some of their wedding presents, a set of fruit knives from the crew of submarine C-14, and a grand silver teapot from the officers of submarine depot ship HMS Forth. |

|

On Talbot's right in this photograph is his father, and to the bride's left his new father-in-law. To his left is the best man, Lt. Martin Dunbar-Nasmith (later

Admiral Sir Martin Eric Dunbar-Nasmith, V.C., K.C.B., K.C.M.G.) who was awarded the Victoria Cross for submarine operations in the Sea of Marmora. On the extreme right of the picture is Cecil's mother. |

When World War 1 broke out in 1914 he was already at sea as a Lieutenant Commander, captain of submarine E-6 (see photos beginning on page 4), in the Heligoland Bight off the North coast of Germany. E-6 and two other submarines were part of a naval force hoping to lure German naval ships out of their bases to prevent them attacking shipping in the Dover Straits carrying the British Expeditionary Force to France. He was Mentioned in Despatches (see Medals and Honours page) for his part in the event. The German ships did not leave port, but he at one stage did see, through his periscope, four large ships moving at full speed directly towards him. He had received no information of any surface ships in the area, and was justified in assuming that they were German. He therefore prepared to fire torpedoes. Only at the last moment did he identify the White Ensign and aborted the action. This avoided a potential disaster of huge possible consequence. For the next 18 months or so, my father was committed to submarine patrols in the North Sea from Harwich. On July 26, 1915 in E-16 he sank a torpedo boat, SMS V-188, and was awarded the D.S.O. (see Medals and Honours page). During a later patrol, after dark on September 15, 1915, also in submarine E-16, he came across the German submarine SMS U-6 on the surface charging batteries (an essential daily routine). He torpedoed the submarine, rescued five of the crew and took them to his base at Harwich (see photos on page 8). This humanitarian action was exceptional, as it could have put his own submarine at risk. My fahter is quoted on the official despatch as "having patience, judgment and skill in a dangerous position". This Daily Mail cutting (see last image on page 8) refers to the "Q" ship incident on August 15, 1915 when The Royal Navy had been accused by the Germans of "Ungentlemanly Conduct" by HMS Baralong, which, disguised as an American merchant ship, had surprised and sunk the German submarine SMS U-27 and shot the survivors. By contrast the press cutting shows the crew of E-16 rescuing the five survivors of SMS U-6. On another occasion, September 25, 1915, in the words of the official report "diving, fouled a mine laid by the enemy. On rising to the surface she weighed the mine and sinker.. the mine was securely fixed.. fortunately the horns of the mine were pointing outward.. The weight of the sinker made it a difficult and dangerous matter to lift the mine clear without exploding it, but after half an hour's patient work the released mine descended to its original depth". Finally on December 22, 1915 Talbot and E-16 sank the 150 ton tug Elbe. To prevent other ships going into the same trap, he sent off a carrier pigeon to report the minefield to the Admiralty. The pigeon flew to its owner in Essex, who unwrapped the message and bicycled with it to the local post office, whence they tapped out a telegram to the Admiralty. (Wireless was in its infancy, and communi-cation with submarines was a real problem, except perhaps by pigeon, a clever ruse originated by my father). Subsequently in 1918 he was awarded a bar to his D.S.O. (see Medals and Honours page). In the words of the official citation. This was "For his skill and coolness in freeing his boat from this obstruction, for long and arduous service in command of submarines, for torpedoing a German destroyer and other operations". Cecil was then promoted to Commander "specially for war service". This meant that he was promoted regardless of seniority, and this was to give him another boost to the rest of his career. He kept a diary/ship's log throughout World War I which is held by the Imperial War Museum. There are also several references to his wartime exploits in the Museum's "The War at Sea 1914-18". Life at sea in submarines was very tough. Hardly any space, wet, cold, tired, lack of sleep, rough seas, bruised, and very high risks. Crew members took turns in "hot" bunks. As volunteers they earned every penny of their extra pay. |

|

Commander Cecil P. Talbot, D.S.O. and sons Frank and Bob c.1916-1917. |

Considering the many casualties suffered by the navy and the army in 1915 and 1916, it was a blessing that my father was appointed to the relative safety of the Admiralty in 1916 and promoted to Captain. During the last two years of World War I and subsequently, he worked as a staff officer in the submarine branch of the Admiralty. At the time of the Armistice he was Captain of the submarine depot ship HMS Ambrose and its flotilla of ten submarines. So his life became less hectic towards the end of the war in November 1918. But the war had hit the Bradshaw and Talbot families hard, my mother's brother, Bartle (2nd Lieutenant Bartle Bradshaw, Border Regiment, 3rd Battalion, killed June 11, 1915) had been killed in the Dardanelles and two of Dad's brothers killed in France; Ted in the army (Major Edward C. Talbot, 47th Sikhs, killed Apr. 29, 1915), and Fitz in the Royal Flying Corps (2nd Lieutenant Reginald F. Talbot, Royal Flying Corps, 19th Squadron, killed Aug. 27, 1916). In the post-war years between 1918 and 1924, he had various short sea commands including HM Ships Bristol, Conquest and Inconstant (see photos beginning on page 11). During this period his family lived in his father's house, 89 Philbeach Gardens SW 5. In 1925, he moved the family to Kirkstall, The Crescent, Alverstoke, near Gosport and the submarine depot. I was born there; My father took command of HMS Hermes and they sailed via Malta to Hong Kong at short notice due to concern regarding China's stance towards the Colony. |

After that he was on half pay for several months, living at home at Culver Lodge in Plympton, near Plymouth. In 1926 he handed over command of HMS Hermes and was appointed head of the Naval Air Section at the Admiralty. Concurrent with this appointment in London he was a naval ADC to the King. This required him to attend various formal functions at Buckingham Palace. So he was then addressed on an envelope as Captain C. P. Talbot, D.S.O., A.D.C., R.N. His next appointment, in 1929, was as captain of HMS Renown (26,500 tons), one of the Navy's two largest and fastest battle cruisers. The ship had a crew of 850 (and it was said that he knew all their names). |

The ship's home port was Plymouth and the ship was part of the Home Fleet, exercising around the British Isles with battleships, cruisers and destroyers. I remember as a four-year old proudly watching the Renown sailing into Plymouth Sound while he was the captain. He was fortunate to have this command during the financial recession when unemployment was rife and the services were being cut back. He handed over at the end of 1930 with a glowing report: "An exceptional and very capable officer strongly recommended for promotion". "He has been a great success, I am very sorry to lose him" wrote Vice Admiral Sir Dudley Pound. The crew gave him a great send off, and the cooks gave me a huge birthday cake made as a model of Renown. Sadly the marzipan went sour so we couldn't eat it. In 1931 he attended a long course for senior officers from the three services held at the Imperial Defence College in London. He was praised for his contributions to the course. Then my father was on half pay for six months. Literally that, half of not very much; service pay was very modest. |

Frank and Bob were cadets at Dartmouth (happily a boarding school without fees). I remember prancing round the nursery table to New Orleans jazz on the gramophone, and my father laying out the white lines for a grass tennis court, using Pythagoras's theorem. In 1932 to everyone's rejoicing he was promoted to flag rank, and Rear Admiral C. P. Talbot, C.B., D.S.O. (see Medals and Honours page), the youngest admiral since Nelson, became Director of Naval Equipment in the Admiralty. This made him responsible for the procurement of boats, wireless equipment etc., everything short of the products of Naval Architects. Vice Admiral Henderson wrote "Rear Admiral Talbot is an exceptional administrator and he has performed his duties most satisfactorily. He has great tactical knowledge and a firm grip on his department and his judgment is sound". We moved from Devon to 419 Upper Richmond Road, Putney. Barbara went to St. Paul's Girls School in Hammersmith. He then went to Fort Blockhouse, the submarine base at Portsmouth, as Flag Officer Submarines. We moved house again, to Bury House, Alverstoke, and I went as a boarder to Brambletye, near East Grinstead and subsequently to Radley, near Oxford. My father at the young age of fifty two and a vice admiral was told that there were no further naval appointments suitable for him. However there was a job for a retired officer as Director of Dockyards with a ten year contract on retired pay. Although this was an Admiralty appointment, their lordships considered that it would be appropriate for a negotiator with trades' union officials to wear plain clothes. Once again we moved house, this time to Orchard Mains, Woking and he commuted to London. Before starting the job he took my mother on a voyage to visit the installations at Trincomalee in Sri Lanka, Singapore and Hong Kong. In addition to these places he assumed the great responsibility of overseeing the repair of ships in ten other dockyards worldwide. A particular problem was the repair and renovation of the fifty laid up destroyers which had been offered by President Roosevelt to Churchill for the war effort. Much worse was living with the knowledge that Frank (HMS Thames) August 1940 and Bob (HMS Snapper) February 1941 both went down with their submarines. |

|

1936 Left: Sub-Lieutenant Edward "Bob" Bartle Talbot, missing in HMS Snapper N-36 since February 12, 1941. Center: Vice Admiral Cecil P. Talbot, C.B., D.S.O. Right: Lieutenant Francis "Frank" Robert Cecil Talbot, missing in HMS Thames N-71 since July 22, 1940. |

He retired from the Dockyards in 1947 and was awarded the K.C.B., in the same year the Netherlands gave him the Order of Grand Officer of Orange Nassau (see Medals and Honours page). So what of the man? There is no doubt that my father was a brilliant pupil who excelled as a Dartmouth cadet, winning just about every prize open to him, thus opening up a Naval career matched by few. He was also extraordinarily lucky in not being seriously injured or killed on several occasions, the first of which was during his rescue of a rating whilst a midshipman in HMS Glory in 1901. The collapse of HM Airship No. 1 "Mayfly" in 1911 could have left him injured or even killed, but he got away from that disaster as well. Then in 1913 he survived an explosion aboard HMS E-5 during her trials, in which three sailors died. On other occasions, such as the time his submarine was entangled with a mine, he used up another of his nine lives. His two brothers, Fitz and Ted, and his brother-in-law Bartle, were not so lucky; the three of them were all killed in the Great War. In 1919, just after the end of World War I, my father gained promotion to captain, a rank in which he remained, due to naval cutbacks, until 1934, when he gained flag rank. Despite being a captain for so long he still became the youngest admiral since Nelson, on top of which he was promoted to vice admiral only two years later. Year by year he received outstanding Confidential Reports (which are now in the public domain). The "limbo" in which he found himself from 1919 to 1925 must have been very tedious but there was also the comfort of being able to spend more time with his family. Then came the honour of commanding HMS Hermes, becoming the head of the Naval Air Service and subsequently commanding HMS Renown. So to what effect did his career to this point have upon his personality? Submariners are by their very nature, and captains of ships (and he was captain of any ships he was appointed to subsequent to his first command) are particularly lonely as convention has it that they live and eat alone, not with their crew, nor even in the wardroom. Despite this he was known to be immensely popular with all ranks, and a strict but fair officer; he was also well known for his natural courtesy and modesty. However, his luck did not desert him; he at least remained in the Royal Navy whilst many of his colleagues, including his brother Frank were retired, or "axed" as the word was used. In 1954 my parents moved from Woking to Penberth near Land's End, to a cottage called Chynance to be close to Barbara and her submariner husband Richard Favell and their families. My mother died in 1960 and my father moved in to live with Barbara and Richard. He kept himself fit walking the dogs walking along the cliffs. He died in 1970. Cecil P. Talbot is buried next door to my mother in the graveyard at St. Levan's Church, between Penberth and Land's End. I am much blessed to have married Jan, the daughter of Lt. General Sir W. Wyndham Green, KBE CB DSO MC DL, and Lady Green. He had a distinguished career in two World Wars, and we have three active Talbot sons and ten grandchildren. |

|

Vice Admiral Sir Cecil Ponsonby Talbot, K.C.B., K.B.E., D.S.O., seen at his home in June 1953 in full dress for the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. |

-2010 Colonel John Talbot All text and photos © 2010 John Talbot all rights reserved |

Note: The Vice Admiral Sir Cecil P. Talbot photo gallery contains images of events mentioned but not shown here. |

Page published Apr. 11, 2010 |

||

© 2005-2024 Michael W. Pocock and MaritimeQuest.com