|

Late September marks the end of the tourist season in Europe and Americans begin to come home, at least that is the way is was in the 1850's. With that in mind the only way to travel was by ship, your choices were sailing ship or steamship, neither a great way to travel, but the paddle steamer was becoming more reliable and was much quicker than the sailing ship. On the 20th of Sept. 1854 the Collins Line sidewheel steamer Arctic left Liverpool bound for New York, Arctic was one of the fastest ways to get home as she held the Blue Riband (eastbound) and had done so since Feb. 17, 1852, her sister Baltic held the westbound record. Her dimensions were an overall length of 298' with a beam of 45' 9", her two cylinder side lever steam engine, built by Novelty Iron Works, delivered about 2,000 horsepower to her two paddles. Registered at 2,856 gross tons she could make 12 knots and could carry 280 passengers with a crew of 145. She was one of four steamships owned by the Collins Line, the others being Atlantic, Baltic and Pacific. The namesake of the line, Edward Knight Collins, had owned the Dramatic Line which operated sailing packets, but he had bigger dreams and a chief competitor to beat, Samuel Cunard. Collins had tried as early as 1841 to convince the U. S. Government to subsidize steamships to cary the mail, he even proposed ships twice the size of Cunard's, but congress declined to approve the $15,000 per voyage Collins was looking for. Cunard still owned the north Atlantic mail service and had proved steamships to be a reliable and fast way to deliver the mail, but the U. S. Government began to change its way of thinking on this subject and decided in 1846 that maybe they should back an American company and not leave the mail solely in British hands. They awarded a mail contract to Edward Mills and his ships Washington and Hermann. The ships, while larger than the Cunard ships, were slower and with the introduction of Cunard's America, Cunard retained the best of the mail contracts. In 1847 the congress finally awarded Collins a mail contract for $385,000 per year with the order to "beat Cunard," which he fully intended to do. There were considerable obstacles to overcome in Collins' quest for the biggest and fastest steamers on the high seas, the first was where to get them. American ship yards were building the finest sailing ships in the world, but only a few were building steamships. The best steamers were built on the Clyde in Scotland however the law prevented him from purchasing foreign built ships so he had to have them built in America. The second problem was money, while the contract would help pay for the operation of such ships it would not build them, that would require almost $3,000,000 which Collins did not have. He did however have a close friend, James Brown of the Brown Brothers banking house in New York. Brown invested $200,000 of his own money and raised over $1,000,000 with a stock offering. Loans of $2,000,000 that Brown arranged completed the funds required to build the four ships. Collins sold all his holdings in the Dramatic Line and with an additional $20,000 from his father in law invested $200,000 as well. With money in hand shipbuilders were found in New York. William H. Brown (no relation to James Brown) and Jacob Bell agreed to build the ships. Atlantic was launched first at Brown's yard followed by the Arctic, also at Brown's yard, Bell built the other two. In keeping with Collins' drive for the biggest and the best he built ships 800 tons larger than the mail contract called for and had much more powerful engines built as well. When finally in service the ships of the Collins Line were considered the finest ships on the north Atlantic. While the interior was opulent the machinery turned out to be less than expected. Frequent breakdowns and stress to the hull caused by the powerful engines caused delays and cancellations which damaged the reputation of the Collins Line. This coupled with the high operating cost kept the line running in the red and in 1852 Collins went back to the government for a raise in the mail contract. After many months of congressional lobbying and a visit to Washington by Collins on the Baltic, his contract was increased to $858.000 per year. He had saved the line. When the Arctic sailed from Liverpool Collins' family was on board, also on board was the family of James Brown. The Arctic was under the command of James C. Luce, a long time veteran of the sea but rather new to steamships. The voyage went fine until she ran into a dense fog south of Newfoundland on the 27th. Even though visibility was nil the captain failed to slow down and therefore endangered his ship. A year before the Arctic had nearly collided with sailing ship in the same area, again fog was the problem. This time Arctic would not be so lucky. A little after noon the French steamship Vesta emerged from the fog on the starboard side. The helm was put hard over to starboard (which turned the ship to port), this action was too late and exposed Arctic's side to the bow of the Vesta. The French ship rammed Arctic on the starboard side 20' aft of the stem. Orders to stop the engine then reverse it caused the two ships to grind against each other and when they separated Arctic had three holes in her hull. Luce sent a man over the side to determine how large the holes in his hull were. He had a total of 434 people on board, but the six lifeboats could hold less than 200. Luce sent a boat with his first officer and a few men to check on the Vesta, which he believed was about to sink. Vesta's captain, Alphonse Duchesne, attempted to lower two of his boats since he also believed his ship was sinking. One of the boats capsized when launched and killed several of those on board, the second boat made it into the water unharmed. While all this was happening the crew of the Vesta had managed to seal the damaged bow and save the ship, on board the Arctic things were much different. Luce had ordered anchors, chains and other heavy items cut away and tossed overboard to lighten the bow, he also ordered passengers to the stern in an effort to raise the bow out of the water to allow the holes to be plugged. All of this failed and the Arctic continued to sink by the head. Luce now made a decision that would be fatal to most of those on board. He decided the only way to save his ship was to make a full speed run to Cape Race about 60 miles away. He ordered the engines to full speed and began his run. Out of the fog came the lifeboat from the Vesta, tragically it was run down killing all but one man who was thrown a rope. Arctic now running at full speed was forcing water in faster and faster, two hours later it reached the boilers and put out the fires. Arctic now at half power was doomed, soon she would sink and everyone knew it. The rule of the sea is women and children first and on this day there were one hundred and nine on the Arctic however, the crew, in an appalling display of cowardess, chose to save themselves and disregard the safety of the passengers. Luce made several attempts to bring his men under control, but according to accounts he was not a strong leader but a gentleman, qualities admired, but not suited for the job of a tyrant, which was needed now. It should be noted that not all of the crew abandoned the passengers. It was now chaos on the Arctic, as they attempted to launch the remaining boats further disasters took place. One boat with Collins' wife and children, fell into the ocean after the lines broke, another boat was sucked into the paddle, still running, and all in the boat were chewed up by the paddle inside the paddlebox. No one who survived would ever forget the unbelievable screams and gruesome sight of this event. The chief engineer, a man named Rogers, followed by some of his men from the engine room, commandeered a small boat from the deckhouse and launched it, keeping others away at gunpoint. While another crewman, third mate Francis Dorian, made a raft on which about 75 people boarded. And engineer Stewart Holland stayed at his post, firing the signal gun, making no attempt to save himself, until the ship went down. Capt. Luce had his 11 year old son Willie with him on the ship. The boy, who was crippled was with his father on the paddlebox when the ship went under and both made it into the water. However the cruelty of the sea would not spare Luce from one final blow. The paddlebox broke loose from the ship and bobbed to the surface landing on his son's head, splitting his skull open and killing him before his father's eyes. In all six boats had been launched from the Arctic, three were never found. Two made it all the way to Newfoundland while other ships picked up one lifeboat and several other survivors. The boat taken by the chief engineer vanished into the fog and was never found. Only one man, Peter McCabe was found alive on the raft by a passing ship twenty-six hours later. Collins not only lost his ship he also lost most of his family. His wife and two of his three children were killed when the lifeboat crashed into the sea. Her brother and his wife were also lost. For James Brown the toll was just as bad. Two daughters and a son, the son's wife and two grandchildren were all killed. Brown's wife went into shock when she received the news and did not speak for over two years. Of the 281 passengers on board only 23 survived while 61 of the 153 crewmen did. None of the 109 women or children survived. The Arctic tragedy did not end the Collins Line, but it contributed to its demise. It took the loss of the Pacific in Jan. 1856 and continued breakdowns and delays to sink the Collins Line, they ceased operations in 1858. |

© 2007 Michael W. Pocock MaritimeQuest.com |

|

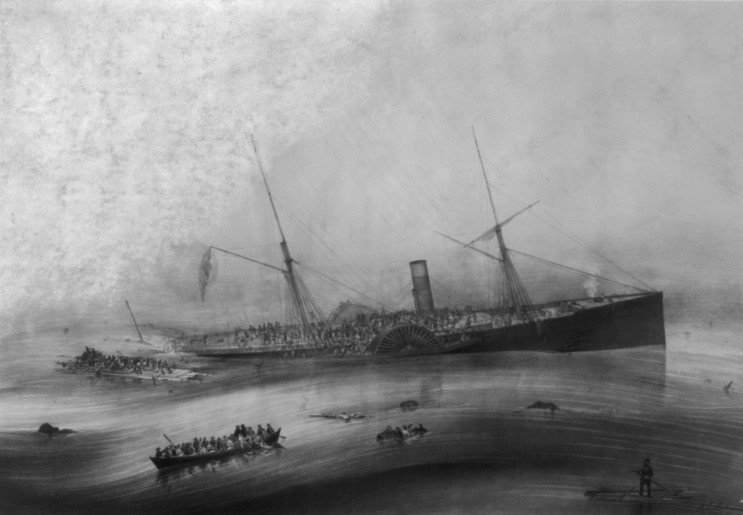

Portrait of the sinking of the Arctic. (Note that Arctic actually had three masts.) |

2006 Daily Event |

||